by Dr John Baily

Freemuse (Freedom of musical expression), London, April 24, 2001

The people of Afghanistan under Taliban rule are subjected to an

extreme form of music censorship. The only musical activity

permitted is the singing of certain types of religious song and

Taliban "chants".

The report traces the gradual imposition of music censorship

since 1978, when the communist government of Nur Ahmad

Taraki (the correct name is Noor Mohammad Taraki -RAWA) came to power in a violent coup d'etat. During 14 years

of communist rule, music in Afghanistan was heavily controlled

by the Ministry for Information and Culture, while in the refugee

camps in Pakistan and Iran all music was prohibited in order to

maintain a continual state of mourning. The roots of the Taliban

ban on music lie in the way these camps were run.

In the Rabbani period (1992-1996) music was again heavily

censored. In the provincial city of Herat, which the author visited

for 7 weeks in 1994, professional musicians had to apply for a

licence, which specified the kinds of material they could perform,

songs in praise of the Mujahideen and songs with texts drawn

from the mystical Sufi poetry of the region. This cut out a large

amount of other music, such as love songs and music for

dancing. The licences also stipulated that musicians must play

without amplification. Music could be performed by male

musicians at private parties indoors, but Herat's women

professional musicians were forbidden to perform. While in

theory male musicians could perform at wedding parties or

Spring country fairs, experience had shown that often in such

cases the agents of the Office for the Propagation of Virtue and

the Prevention of Vice, religious police, had arrived to break up

the party and confiscate the instruments, which were usually

returned to the musicians some days later when a fine or bribe

had been paid.

There was very little music on local radio or television in Herat.

Broadcasting time was anyway severely curtailed, to about two

hours per day. If a song was broadcast on television one did not

see the performers on screen but a vase of flowers. Names of

performers were not announced on radio or television.

Instrument maker had re-opened their businesses, and the audio

cassette business continued, with a number of shops in the

bazaars of Herat selling music cassettes, some of locally

recorded Herat musicians.

"To prevent music... In shops, hotels, vehicles and

rickshaws cassettes and music are prohibited... If

any music cassette found in a shop, the shopkeeper

should be imprisoned and the shop locked. If five

people guarantee, the shop should be opened, the

criminal released later. If cassette found in the

vehicle, the vehicle and the driver will be

imprisoned. If five people guarantee, the vehicle will

be released and the criminal released later.

To prevent music and dances in wedding parties. In

the case of violation the head of the family will be

arrested and punished.

To prevent the playing of music drum. The

prohibition of this should be announced. If anybody

does this then the religious elders can decide about

it."

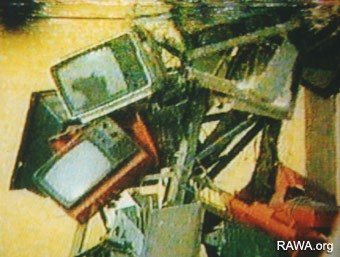

All musical instruments are banned, and when discovered by

agents of the Office for the Propagation of Virtue and the

Prevention of Vice are destroyed, sometimes being burnt in

public along with confiscated audio and video cassettes, TV sets

and VCRs (all visual representation of animate being is also

prohibited).

The only forms of musical expression permitted today are the

singing of certain kinds of religious poetry, and so-called Taliban

"chants", which are panegyrics to Taliban principles and

commemorations of those who have died of the field of battle.

These chants are themselves highly musical: the singing uses the

melodic modes of Pashtun regional music, is nicely in tune,

strongly rhythmic, and many items have the two-part song

structure that is typical of the region. There is also heavy use of

reverberation. But without musical instruments this is not "music".

The effects of censorship of music in Afghanistan are deep and

wide ranging for the Afghans, both inside and outside the

country. In the past, the people of Afghanistan were great music

lovers and enjoyed a rich musical life. Music was an integral part

of many rites of passage, such as celebrations of birth,

circumcision (male only), and most important of all, marriage.

Only death was a rite of passage lacking in musical expression.

The lives of professional musicians have been completely

disrupted, and most have had to go into exile for their economic

survival. The continuation of these rich musical traditions is also

under treat.

The report makes the following recommendations.

(1) To highlight the critical situation as it exists today.

(2) To try to give musicians both inside and outside

the country economic support, and in the

transnational communities, to persuade aid agencies

of the importance of music in the lives of refugees.

(3) To make sure that what is left from the past is

adequately documented, so that something is left

for the future.

(4) To support the craftsmen who make traditional

Afghan musical instruments, for traditional music

cannot be played without the appropriate

instruments.

(5) To support practical musical education

programmes in the transnational community and to

persuade the relevant agencies of the importance of

music coping with the traumas of refugee life.

When the Taliban took control of Kabul in 1996 a number of

edicts were published against music. For example:

When the Taliban took control of Kabul in 1996 a number of

edicts were published against music. For example: