Repression and RAWA:

A View of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan

The original article covers few more photos. -RAWA THE SETTING:

Peshawar, Pakistan.

October 2000

A frontier town near the border of Afghanistan, for centuries a centre for travellers and traders, smugglers and soldiers, a history inextricably linked with the Khyber Pass, on the silk route, spice route, opium route, dating back from Buddhist, Mughal and Sikh times. The old city: a mosaic of bustling bazaars, crammed with people, objects, animals and stories of every kind imaginable. Buildings with intricately carved wooden doors, balconies, line the narrow, winding streets, and kebab stalls, spice shops and perfume sellers fill the air with intriguing scents.

I am buzzing through the streets in an auto rickshaw with a woman whose real name I do not know, she has no fixed address and cannot tell me where we are going. We stop at a butcher’s shop, negotiating the huge shanks of raw meat hanging from hooks above the doorway. A few men, tall and rather fierce-looking, lurk near the entrance eyeing us suspiciously, then one tells us to sit down. An enormously fat man with a bushy beard and shifty eyes sits behind a large copper samovar from which he dishes out cups of kawa – green tea - for all of us. I sip my tea while things are whispered, glances exchanged, arrangements made. We set off in another auto, this time accompanied by a man. As usual, I am not introduced to him. The less information exchanged, the better. More winding streets and another stop, this time at a tailor’s, again the same process. They speak in about four different languages: Pashto, Dari, Urdu, Pashai and there’s no way I can understand a thing. The streets are so labyrinthine, that I don’t know where we’ve been even if we’ve been there; but I am taken: by the amazing sights, scents, atmosphere: all is mysterious, exotic, romantic, most of all, dramatic.

It could be the set of a James Bond flick.

But it’s not.

A few months ago I would never have believed it possible: I was in LA (where I’ve lived for the past 20 years) and had gone to a bookshop to hear a couple of representatives from RAWA, an Afghan women’s rights group. They were on a speaking tour around the States, and I was so impressed by their presentation, and so appalled by the situation that they described, that I went to talk to them afterwards. When they offered to show me around Pakistan, and asked me if I might be interested in making a documentary about the condition of Afghan women, I jumped at the chance. That’s how I find myself, a few months later, sitting in that little auto, armed with a mini DV camera, a compact wireless mike system, a light tripod and a vague plan for a documentary.

I must admit, that as well as my excitement, I was also apprehensive about going to Pakistan on my own.

The US State Department had issued a travel alert against Pakistan that read: ‘Unsafe for travel, especially not recommended for single women’. I was afraid that my camera equipment might be confiscated at the airport, that I’d have to bribe the immigration officials, and then be imprisoned for trying to; such were media reports about the country. The travel alert warns against going to the ‘tribal areas’ where the Khyber Pass is located, saying it is so dangerous that even the Pakistani government has no jurisdiction there – it is controlled by bands of roving Pathan tribesmen. A spate of recent magazine articles focused on Peshawar specifically, describing it as a hotbed for terrorism, drug smuggling, arms-trading and random violence. Supposedly it was easier to buy a rocket launcher than a pair of socks in this town.

Many of these notions were soon dispelled. Arrival was easy, clean airport, polite staff, immigration officials all smiles, no hint of bribe expectation. Camera equipment not even questioned. As far as reports of violence, drugs, etc, it’s there, but no more so than say, New York. Prevalence of guns - it’s a lot easier to find one in America; and as for the dreaded tribal areas – they seemed far safer to me than many parts of Los Angeles. I don’t want to trivialize the more sinister aspects of what is happening, but for the most part, media reports are overblown to say the least.

I find myself wearing two hats as a videomaker: one, I was completely taken with the ‘picturesqueness’ of Peshawar; the air of mystery and romance associated with it still exists, and visually it is stunning. The other hat though, is more down-to-earth. The exotic, clandestine meetings, pseudonyms, changes of address and escort, holds a sense of adventure for me, but I soon realize that RAWA is not in it for the glamour: this is their real life. They have to take these precautions because they fear for their lives. It is necessary, it is mundane, and living this way every day of their lives, it is difficult.

Which brings me back to the auto-ride described above. All those arrangements, the stops, the changes of autos, etc, were not to score drugs or arms, but just to visit an orphanage. The woman accompanying me was a member of RAWA. Known to me as ‘Sahar’; she was my guide, and interpreter, and became a very close friend. The orphanage is one of several in Pakistan run by RAWA. It houses about 30 Afghan children all of whom have lost either one or both parents in the fighting. The children receive shelter, and also clothing; food and as good an education as one can hope for under dire circumstances.

I was in Pakistan for 6 weeks and was able to interview many people from different walks of life; from prostitutes and beggars to politicians and journalists, Marxists to Mullahs, refugees to ambassadors and consuls.

But the women of RAWA are the real heroines of this story. Their work, their courage is remarkable; what they achieve with few resources, working under such adverse conditions is quite unbelievable. They have positively affected the lives of hundreds of women and their families, and provide, in my opinion, one of the only rays of hope in an otherwise bleak situation.

RAWA stands for the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan. Apparently the word ‘revolutionary’ is problematic for a lot of people: too ‘radical’, ‘extreme’, ‘militant’. Sahar is baffled by this response. ‘It’s very simple, why we call ourselves revolutionary,’ she says earnestly. ‘What we want is full human rights for women; we want women to be recognized as human beings; in Afghanistan, this in itself is considered ‘revolutionary’. We want a secular, democratic government, with freedom of thought, speech and religion for everybody: this too is revolutionary… People call us ‘radical’ because we remind them that all the Jehadi parties are fundamentalists with a distorted interpretation of Islam, that they have all committed heinous atrocities against their own people, and therefore should not be included in any future government for Afghanistan. We have to be radical, we are fighting the most brutal regime: we have to be absolutely unwavering in our struggle for our rights’.

Founded in 1977 by a highly charismatic woman, Meena, the group has weathered the storms of twenty-two years of war and struggle. Even before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Meena, a committed feminist, poet and health worker, campaigned for women’s rights in Afghanistan. When the Soviets invaded, the work became more crucial, and she and her supporters opened schools, hostels and hospitals for the Afghan freedom fighters. Ten years after founding the organization, Meena was assassinated. It is still uncertain whether she was killed by KGB agents, or the Hizb-e-Islami. Even in death, however, Meena exerts a powerful influence, inspiring women to continue the work she began.

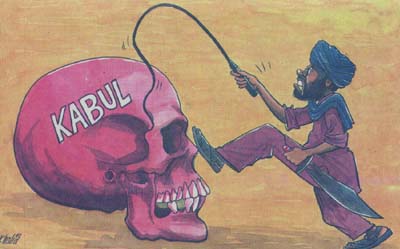

RAWA’s struggle is even greater now under the brutal regime of the Taliban, who are denying people, women especially, basic human rights. The litany of laws restricting the lives of women in Afghanistan are common knowledge now: they are not allowed to work, not allowed to go to school, must live in houses with darkened windows lest they be seen from the outside, cannot go outside without a close male relative, cannot be treated by male doctors so that, since women doctors are virtually non-existent, they cannot be treated if sick. If they are caught breaking these laws, they can be severely beaten, imprisoned or even killed. Beating, rape, even murder of women goes unpunished. Under Taliban law their very existence, it seems, is immoral. A large proportion of women suffer from serious depression and isolation, and many have chosen to take their own lives rather than exist under these extreme circumstances.

RAWA has about 2000 active members within Pakistan and Afghanistan. With very limited resources they manage to provide a broad range of services in their aim to educate women. They run schools for girls that go up to grade 12. They run mobile health clinics, have nurse-training courses, literacy courses for women who missed out on early education. They also promote self-generating income projects, such as providing chickens to women so that they can sell eggs in the market. Handicrafts, sewing, embroidery, carpet weaving are also encouraged. RAWA also gives help and support to prostitutes, recognizing that thousands of women, mostly war-widows, have been forced into prostitution, as working is banned and begging cannot feed them and their children.

All these services are provided at great risk to the members’ personal safety, especially in Afghanistan. There, everything must be undercover. If discovered by the Taliban, they would be put to death immediately. Sahar says ‘It is the only way our women can get an education, can get health care, we have to do this.’ The Taliban and other Jehadi parties have issued decrees for the death of any RAWA member by stoning, equating them with prostitutes. This is why they must work in secrecy, use aliases, and why they cannot stay in one place for too long. They are the only Afghan women’s group working within Afghanistan itself.

RAWA also holds rallies, protests and demonstrations in Pakistan to draw attention to the plight of Afghan women. These are usually well attended, drawing crowds of up to five thousand. Their male supporters act as bodyguards and escorts and are fully supportive of their aims. RAWA also publishes a magazine and holds cultural events, and, increasingly, members are invited to attend international conferences and seminars.

Recently RAWA has begun a new project, that of video documentation. In November 1999 a woman in Kabul was sentenced to death for suspected adultery. All the women of Kabul were summoned to watch the execution, which took place in a large sports stadium in the centre of the city. A RAWA member smuggled in a video camera under her burqa and managed to record the entire proceedings. Since then other punishments have been recorded: amputations, a hanging, death by throat slitting. No news company will buy or air the footage however, and RAWA is wondering how best to show the world what is happening in their country. There are no easy answers.

Because of their political beliefs, they cannot qualify as an NGO, and so funding is difficult to come by in spite of the humanitarian work they do. Recently they had asked the Pakistan government if they could distribute blankets to the thousands of Afghans who are stuck at the border, which Pakistan recently closed at Torkham. Permission was denied because of their ‘unoffcial’ status. They rely on private donations from individuals for their funding, and on income from magazine sales, and are working on other self-generating income projects.

RAWA’s emphasis on education is central. ‘People need to be educated, they need to be made aware of their condition, that they don’t have to live like this’, says Sahar. ‘The Talibs and Jehadis don’t know anything about the history and culture of Afghanistan. They are denying the people education because they want them to be ignorant, so that they can be controlled.’

While many women welcome their efforts, it is still tough going for RAWA to convince the population of their strong belief in education. ‘Before we can speak to the women, we must first convince their husbands to allow us to even talk to them. Many times, the husbands call their wives ‘half-wits’ and do not see the need for their education’, says Sahar.

Still she is hopeful. She says many Afghans are fed up with the fighting and the war, but they are more fed up with the Taliban and their version of Islam. ‘Even the men’, she says, ‘do not support the Taliban. The men suffer as well. They are severely beaten if they have no beard or if it is too short. If they do not close their shops to pray five times a day, they may be imprisoned. This is not Islam. Islam clearly says women can be educated, can work. Islam clearly states ‘there can be no compulsion in religion’. There are few job opportunities, there’s no infrastructure, and even school for boys is difficult as there are no facilities. Who can live under these conditions?’

I heard countless tales of loss, suffering and hardship. Every Afghan I met had lost at least one, usually more, members of his or her family, to rocket shelling, landmines, combat, torture, rape – the list is endless. Amidst this horror, RAWA’s work stands out as having a very real impact on the lives of people around them. Not only are they affecting them in materially, but morally too: they provide hope, so vital for a war-weary people.

RAWA is also impacting world opinion. With the launch of their website (http://www.rawa.org), they have reached millions of people around the world, gaining tremendous support, some of which translates monetarily. If someone contributes one dollar, it helps, because that dollar can put a girl in school for a month. Every little bit helps.

’We hope that the world will hear our message. We hope that world can hear our stifled voices, and join together with us so that our voices will ring loud and strong against our oppressors. We want to return home to our country, for if we have lost our country, we have lost ourselves. We will work for peace, freedom and democracy in Afghanistan, no matter how long it takes or how many sacrifices we must make, we know that eventually we will win. It is what the people want.’

There are no easy answers, no quick fixes; the refugees will probably not be able to go home for a very long time. Yet there is something in Sahar’s statement that rings true, and eventually, one hopes, will bear out.

To learn more about RAWA please visit their website at www.rawa.org

Meena Nanji is an LA based filmmaker. She is presently in the subcontinent, making a documentary on RAWA.

Acknowledgments:

All the photographs in this article are taken from the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan website.

From:

http://www.digitaltalkies.com/magazine/2001/JAN/1/11/limelight.asp

http://www.greenleft.org.au/current/433p22.htm